His death It was said at the University of Texas at Houston MD Anderson Cancer Center, where Dr. Jordan was a professor. He had kidney cancer, his daughter Alexandra Noel said.

Dr. Jordan, who grew up in England and holds dual British and American citizenship, once he told an interviewer. He “barely made it out of grade school” because of his poor grades.

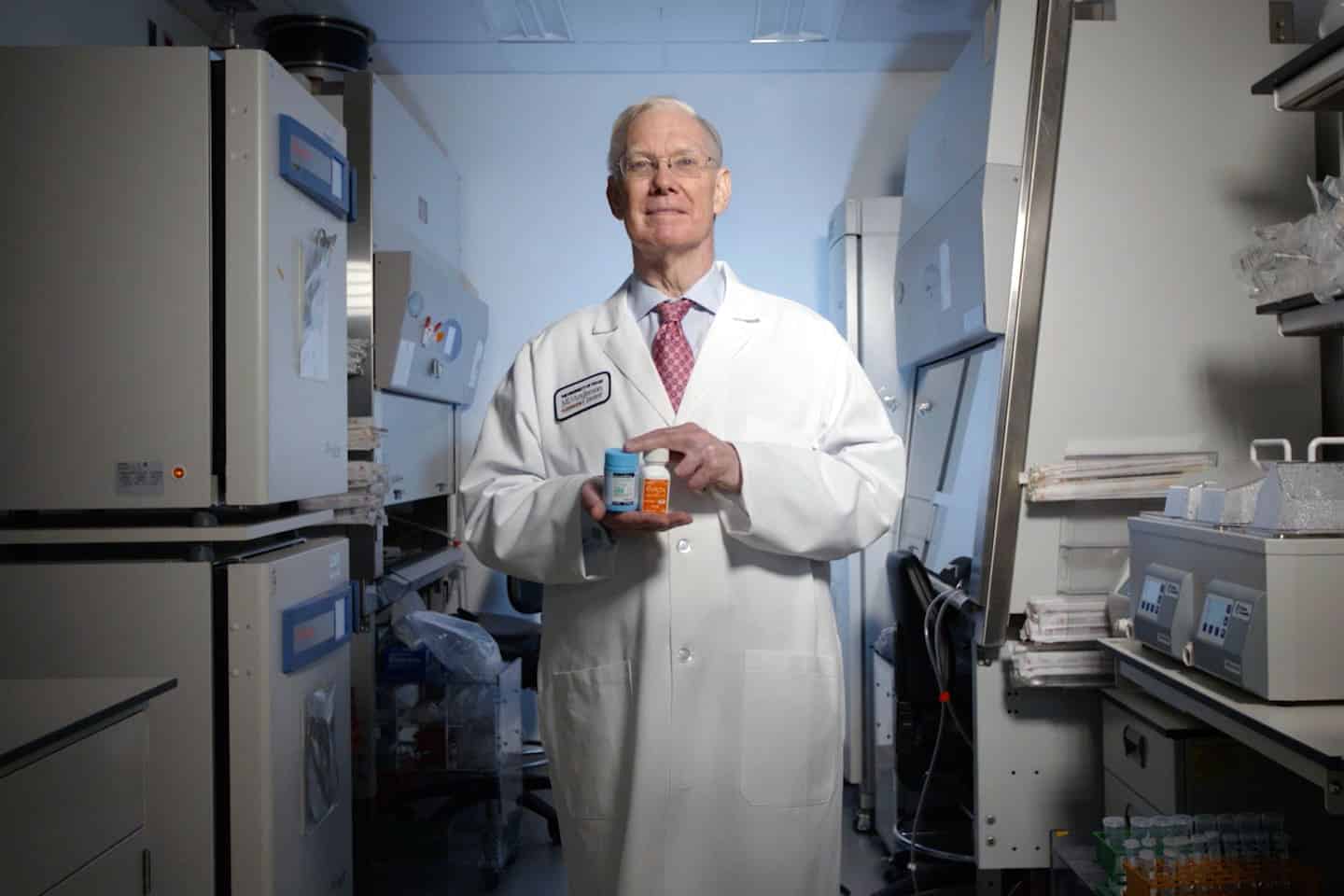

It was not reflected in those early report cards, but it was the curiosity, perseverance and talent of one of the most famous cancer researchers of the second half of the 20th century, who is known as the “father of tamoxifen”. “

When Dr. Jordan began his research in the late 1960s as a doctoral student at the University of Leeds in England, potentially curable cancers were attacked in three main ways: surgery to remove the tumor and radiation and chemotherapy to kill cancer cells.

Breast cancer patients have historically undergone radical and often damaging surgery to remove the breast and surrounding tissue.

Radiation opened new avenues for treatment but came with serious side effects. Chemotherapy, the latest development in oncological care, represented a revolution in medical science but was often cruel to the patient.

“He was obsessed with the idea. [that] Combination chemotherapies used to cure all cancers,” says Dr. Jordan. He told the website. Oncology Central in 2019.

“It looks like we’re trying to swim upstream,” he added, as he and his colleagues try to push scientists to look beyond chemotherapy, which causes relatively isolated attacks on the body, to drugs that target a specific cancer. Cells.

Dr. Jordan unexpectedly demonstrated the potential of his idea on the anti-estrogen drug tamoxifen, which began its pharmaceutical career as an experimental contraceptive.

As a contraceptive, tamoxifen works brilliantly in mice. Dr. Jordan told the Chicago Tribune in 1998 that “the girl who takes it is going to get pregnant,” a dramatic decline in women and “proven.”

“During the sexual revolution of the 1960s, the last thing you needed was for everyone to get pregnant,” he said.

However, Dr. Jordan saw another benefit for tamoxifen and conducted further research. Over the years, it has been understood that some breast cancer patients – those with estrogen receptors – respond well to having their ovaries, which produce estrogen, removed.

Dr. Jordan hypothesized that an anti-estrogen drug may have the same positive effect. In the year In 1973, he showed that tamoxifen could prevent breast cancer in mice.

The following year, human trials were being conducted in the United States. In the year In 1977, the Food and Drug Administration approved tamoxifen for use in advanced breast cancer cases.

In the following decades, it was approved for the treatment of early-stage cancer in conjunction with surgery. In the year In 1998, the FDA approved tamoxifen to prevent relapse in high-risk but otherwise healthy patients.

After Dr. Jordan’s death, the Prevent Cancer Foundation claimed to have discovered “the first FDA-approved drug to prevent cancer.”

Tamoxifen sometimes carries risks, including ovarian cancer or blood clots. But it is ranked by the World Health Organization as one of the most prescribed drugs in the treatment of cancer List of essential medicines.

Tamoxifen is known as a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM). Other SERMs include raloxifene, another subject of Dr. Jordan’s work, used to prevent osteoporosis as well as breast cancer.

Dr. Jordan was born Virgil Craig Johnson in New Braunfels, Texas on July 25, 1947. His mother is English and his biological father, a Dallas man, met while his father was serving in the US Army in England during World War II.

The couple moved to Texas after the war, but divorced when Craig, as Dr. Jordan was always known, was a teenager. He and his mother moved to England, where he grew up in Bramhall, near Manchester. He was raised by his mother and stepfather, who adopted him and gave him the name Jordan.

Despite his poor academic performance, Dr. Jordan developed an early love for chemistry.

“I turned my bedroom into a chemistry lab, but a real chemistry lab with things I got from the pharmacy and got free from school, not one of those kid’s kits.” They remembered years later.

“There were many life-threatening moments when my experiments exploded or caught fire and I had to throw things out the window,” he continued. “But my mother always said, ‘At least we know where he is.'”

He eventually enrolled at the University of Leeds, earning a BA in 1969 and a PhD in 1973, both in pharmacology, where he wrote his PhD on tamoxifen. The university awarded him a Doctor of Science in 1985.

At Leeds University, Dr. Jordan joined the British Army Officers Training Corps. He later served in the Intelligence Corps and the Special Air Service and spent years in the reserves.

During his scientific career, he worked at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill., the Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, and the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center at Georgetown University Hospital before joining the MD Anderson Cancer Center in 2014. .

Dr. Jordan’s marriages to Marion Williams, Monica Morrow, and Julia Jauch ended in divorce. Surviving are two daughters from his first marriage, Alexandra Noel of Stillwater, Minn.; and Helen Turner of Salt Lake City and five grandchildren.

When the lifesaving breast cancer drug became known as “Daddy,” Dr. Jordan regularly encountered people, he told the Houston Chronicle, who told him, “My mom’s on tamoxifen, my wife’s on tamoxifen.”

“Mothers have seen their children grow.” he said. “Grandmothers have seen their grandchildren grow up.”