A pill taken once a week. A shot at home once a month. Even a jab given at a clinic every six months.

In the next five to 10 years, these options may be available to prevent or treat HIV. Instead of drugs that need to be taken every day, scientists are closing in on options that can be taken longer – perhaps in the future, HIV will be twice as important. An unimaginable year in the pandemic’s darkest decade.

“This is the next wave of innovation, where new products are meeting people’s needs, particularly around prevention, in ways we haven’t before,” said Mitchell Warren, executive director of HIV prevention organization AVAC.

Long-term treatments can eliminate the need to remember to take a daily pill to prevent or treat HIV, and for some patients, the new drugs can ease the stigma of the disease, which itself becomes a barrier to treatment.

“That stigma, taking that pill, is an internal stigma,” said Dr. Rachel Bender Ignacio, director of UW Positive at the University of Washington, a clinical research center that focuses on HIV. Every morning, it prevents them from taking.

Long-term medications can be of greater benefit to people who are more difficult to reach: patients with health care problems or patients who have problems with daily pills. Unstable housing or transport, struggle with drug addiction, are mentally ill or face discrimination and stigma.

In the year By 2022, 30 years after the advent of combination antiretroviral therapy, more than nine million 39 million people live with HIV They were not receiving universal treatment. About 630,000 died of AIDS-related illnesses that year.

Even in the United States, about one-third of people infected with HIV cannot control the virus. “We still haven’t addressed these fundamental issues around access,” said Greg Gonsalves, a longtime HIV advocate and epidemiologist at the Yale School of Public Health.

“We can be excited about the science and clinical implications of long-lasting drugs,” he said. But for many people this will be a distant dream.

One barometer of excitement about long-term measures was their prominence at the Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections conference in Denver in March. It served as the starting point for many HIV breakthroughs, including the 1996 Electric Moment, in which researchers showed that a combination of drugs inhibited the virus.

Dozens of long-term studies have been presented this year. (While most such drugs are very close to HIV prevention and treatment, similar options for Tuberculosis(Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C are not far behind.)

A long-term treatment – Cabenuva, two injections every two months – was found for three years. It costs more than $39,000 annually in the United States, although few patients pay that price. However, despite significant reductions, the treatment is out of reach for many patients in low-income countries.

Still, many researchers at the conference were excited by the results of a study that showed Cabenuva was more effective than daily pills in controlling HIV in a group of people who had difficulty adhering to treatment.

“When you think about how difficult it is for some people, it’s a big deal to give them new tools that can make them suffocate,” said Dr. Kimberly Smith, who leads research and development at ViiV Healthcare. One of the drugs in Cabenuva.

Long-acting drugs may be beneficial even for children living with HIV.Globally, only about half of all HIV-infected children are being treated.

That’s partly because of a lack of pediatric versions of the drug, said Dr. Charles Flexner, an HIV expert at Johns Hopkins University, speaking at a conference in Denver.

“Long-acting formulas, that’s not going to happen anymore,” Dr. Flexner said. “Children can use the same spelling as adults, just to a different extent.”

Most long-term recording consists of nanocrystals suspended in a liquid. While oral pills must pass through the stomach and intestines before entering the bloodstream, depot shots deliver the drugs directly into the bloodstream. But they are released very slowly over a period of weeks or months.

Some Depo antipsychotics are given every two to eight weeks, and the birth control pill Depo-Provera is given once every three months. Cabenuva – a combination of cabotegravir, by VV Healthcare (mostly owned by GSK) and Janssen’s rilpivirine – is injected into the gluteal muscles every two months to treat HIV.

Cabotegravir, given under the skin of the stomach, produces sores and rashes, and some people develop nodules that last for weeks or even months. But with gluteal injections, “you don’t see anything,” says Dr. Smith. “You feel pain for two days and then you get on with your life.”

ViiV is trying to develop a version of cabotegravir that is given every four months and eventually one every six months. The company plans to bring a four-month version to market in 2026 for HIV prevention and treatment in 2027.

But injecting drugs into a muscle, as some trans women do, can be challenging for people with significant body fat or silicone implants in their fists. Some new vaccines in development are administered under the skin, eliminating the problem.

Gilead’s lencapavir can be given as a subcutaneous injection in the abdomen once every six months, but so far. Only approved. For people with HIV Resistant Other medicines. The drug is in several late-stage trials as a long-term HIV prevention in different groups, including cisgender women.

Lenacapavir is also being tested as a treatment in the form of A. A pill once a week In combination with another drug, islatravir, manufactured by Merck. “It’s good to have more long-term treatments so people can choose the options that work for them,” said Dr. Jared Beighton, Gilead’s vice president.

Santos Rodriguez, 28, was diagnosed with HIV in 2016 and has since taken a daily pill to fight the virus. Taking just one pill a week is “definitely a tight fit for me and me,” said Mr. Rodriguez, who works on artificial intelligence at the Mayo Clinic in Florida.

He said his visits to the clinic, which required bimonthly follow-ups for Kabinuva, were cut short, and reports said the injections in the buttock were painful. Shooting every four months or every six months would be more attractive, he added.

To make it truly accessible to everyone, including those who live far from health care facilities, researchers need to come up with a self-administered long-acting injection, some experts suggest.

A team is actually building it and plans to make it available in low- and middle-income countries with support from the global health initiative Unitaid.

Dr. Bender Ignacio, referring to the trend in developed countries, said: “The interesting thing about this is that it is able to bypass the rush effect to get to the people who need it the most.” First, finding new treatment methods. She is leading the study.

The product uses a lipid base to block three HIV drugs, two water-soluble and one fat-soluble. Unlike depot shots, which release the drug slowly, this one, called Nanolozenge, is absorbed immediately after birth by immune cells and lymph nodes under the skin of the stomach.

Because of this efficiency, the shots can take small amounts of medicine, and can be easily adapted to children and teenagers, said Dr. Bender Ignacio. One syringe replaces 150 capsules and contains more than a month’s worth of the three drugs.

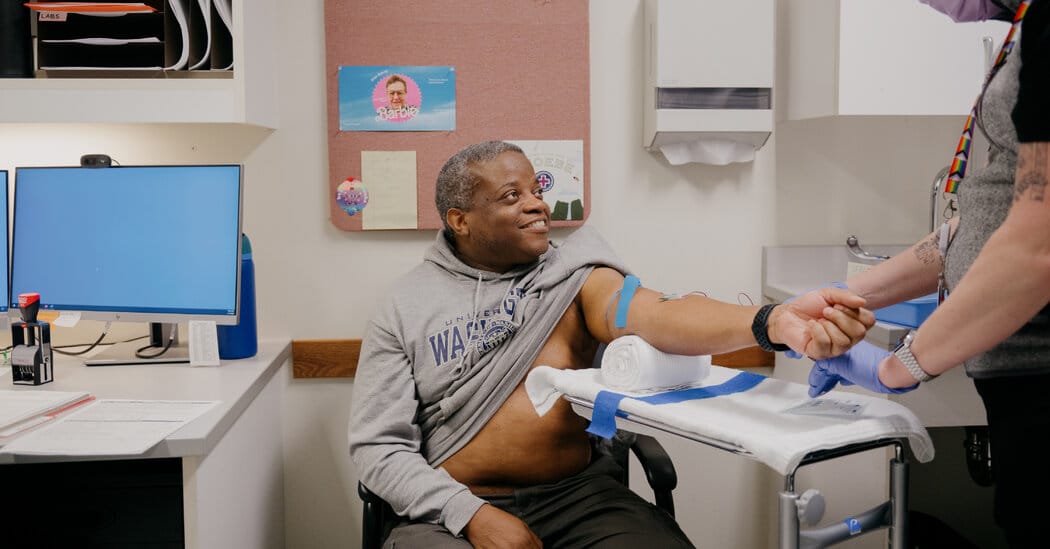

So far, the self-administered long-acting shot has been tested on only 11 people, including Kenneth Davis, 58, of Auburn, Wash. Mr. Davis, who lost two family members to AIDS, likens the jab to a bee. Injections – temporary and less painful than covid vaccines.

Because the drugs that make up the drug are each approved independently, Dr. Bender Ignacio estimates that vaccines will be available to treat HIV in less than five years.

Many of the products, including those found in Dr. Bender Ignacio’s research, can be adapted to prevent HIV. Currently, there are only three options for that: two types of daily pills and ViiV’s cabotegravir, which is injected into the anus once every two months.

“The biggest step back in the AIDS response over the past decade has been prevention,” said Mr. Warren of the AVAC.

A study presented at the Denver conference showed that when people were given a choice of prevention methods, most chose long-acting cabotegravir. But the percentage opting for daily pills has also increased.

“The way we look at conservation is that it goes with different methods – that’s the most important thing to me,” Mr. Warren said. The study added, “In fact, it now shows that there is evidence behind the choice, not just advocacy.”