Discussion

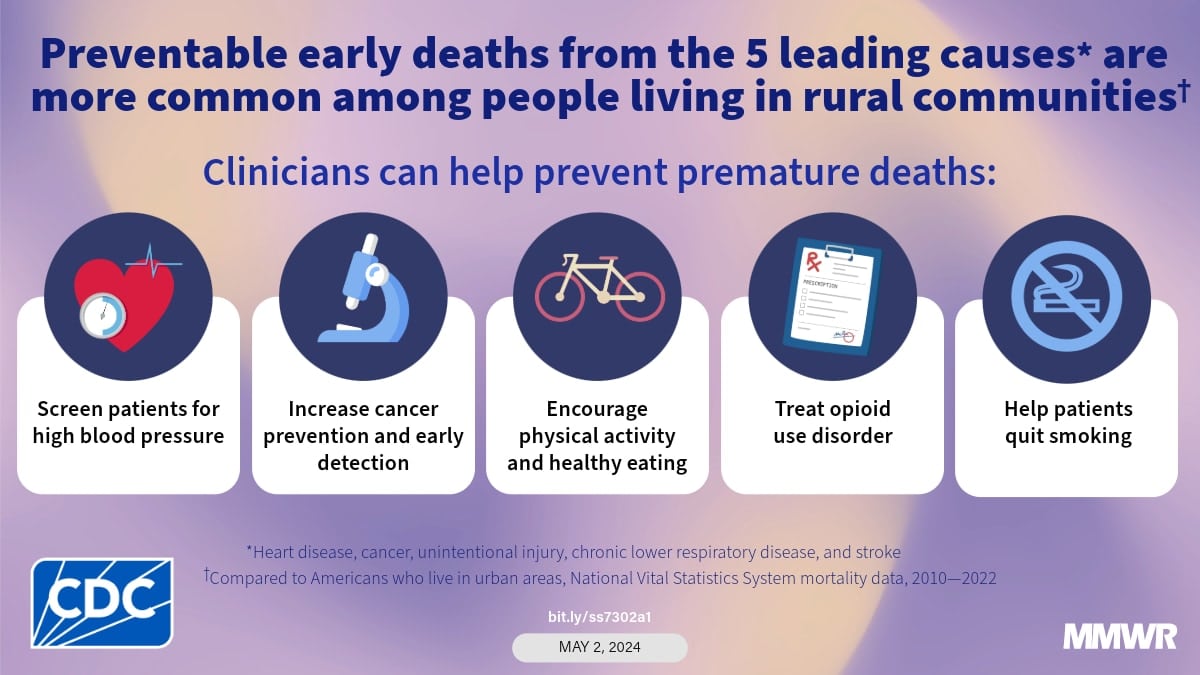

Rural residents, particularly those in disadvantaged counties, experienced a higher percentage of preventable premature deaths during the study period. Rural-urban differences in premature mortality vary by cause of death. However, the differences were not limited to the place of residence. Disparities in premature mortality are associated with other demographic factors (eg, gender, race, and ethnicity).11). For example, rural counties where the majority of the population is black, African American, American Indian, or Alaska Native have the highest rates of premature death.11). To address rural-urban premature mortality disparities by rural-urban county category, race, and ethnicity, data on cause-specific differences in premature mortality from the five leading causes are needed to inform race-specific interventions and health care policies. and nationalities. This disaggregated analysis by race and ethnicity will emerge in future reports, providing additional evidence to guide existing and new programs and policies.

Cancer

Overall, reductions in premature cancer deaths were greater and greater in urban counties with better access to preventive services, treatment, survivorship care, and specialty care than in rural counties (19). Large central metropolitan and fringe metropolitan areas achieved benchmark rates in 2019, which declined by 27 percent between 2001 and 2020.20). The reduction in preventable premature deaths reflects several factors. Increased screening is recommended for the leading causes of cancer death (eg, lung, colon, cervical, and female breast) to prevent early detection, when treatment is more effective, and to detect and prevent cellular changes before they become cancerous.21). Increasing vaccination rates against cancer-causing viruses and reducing the prevalence of risk factors (such as combustible tobacco use) have led to lower cancer deaths (22). Access to these cancer prevention and detection strategies has increased with the expansion of Medicaid.23). New cancer treatments and therapies, particularly for lung cancer and melanoma, have also led to longer lives for people diagnosed with cancer (24). CDC conducted a demonstration project on how to better care for people diagnosed with cancer in rural areas (25). Although cancer is classified as a single disease group in this analysis, each cancer site has different risk factors, has different treatment options, and may present differently among groups by sex, age, race, and ethnicity. Preventable premature death may vary by cancer site and may not be due to the prevalence of risk factors (eg, obesity), no recommended screening methods, or unchanged treatments for reduced cancers. Lung cancer, the leading cause of cancer death, will account for 23% of all cancer deaths in 2020.20). Geographic differences in combustible tobacco use and use of lung cancer screening may partially explain differences in lung cancer mortality. Access to lung cancer screening facilities is more limited in rural counties than in urban counties (26). Although overall premature deaths from cancer have declined, premature deaths in micropolitan and non-core counties are higher than the national average, highlighting the importance of reducing premature cancer-related deaths in rural areas. In 2019, cancer death rates in many urban areas exceeded 2010 cancer rates, and future revisions to cancer-specific rates using data from recent years may reflect much lower death rates.

Unintended damage

The worsening and expanding epidemic of drug overdoses, increased motor vehicle traffic deaths, and falls have fueled the growth in premature injury deaths (27). The narrowing of rural-urban disparities in the percentage of premature deaths caused by unintentional injuries was exacerbated by urban immunization rates, which doubled in percentages in large central metropolitan areas over the study period. Access to medications for overdose, opioid use disorder, remains very limited in rural counties, reflecting low buprenorphine prevalence and reduced treatment capacity.28). Rural residents are more likely to die in motor vehicle crashes and less likely to use seat belts than urban residents.29). Evidence-based interventions reduce rural-urban differences in seat belt use and motor vehicle mortality (30). Many fall risk factors are modifiable, indicating that many falls are preventable (31).

Heart disease and stroke

During the study, differences were observed between rural and urban areas in terms of treatable premature death from heart disease and cerebrovascular disease. These gaps increased from 2019 to June 2022, except in large metropolitan areas, which saw a three percentage point decrease from 2020 to 2021. – Related conditions that contribute to increased risk-related deaths from heart disease and stroke (32). 2020 compared to 2019 saw an increase in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, the risk factor for heart disease and stroke, among all age groups.33). Inequalities in blood pressure control (i.e., systolic blood pressure values ≥130 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure >80 mm Hg, or both) during the COVID-19 pandemic were observed and associated with inadequate access to health care, medication adherence, and follow-up (34). Patients experiencing a life-threatening event during the COVID-19 pandemic may be delayed in seeking emergency care (35). In the weeks following the declaration of Covid-19 as a national emergency on March 13, 2020, emergency room visits for heart failure and stroke decreased by 20%, and hospitalizations for heart failure and stroke decreased during the outbreak.35). In addition, covid-19 increases the risk of stroke and heart disease (36,37).

Chronic lower respiratory tract disease

In the year The percentage of preventable premature deaths from CLRD remained stable in medium and small urban counties and rural counties during 2010–2015, despite an overall decline in 2010–2020 (due to a decline in large urban areas). In the year During 2010-2022, the number of premature deaths due to CLRD that could have been significantly prevented in urban areas from 2019 to 2021 and deaths due to Covid-19 that otherwise could have been caused by CLRD. People with CLRD (eg, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) have a higher risk of dying from Covid-19.38).